| BIRTH | Pierre (Peter) I "MAUCLERC" or "MALCLERC" DE DREUX[19,26,41,42] was born in 1191[19,43] He was the second son of Robert II, count of Dreux. The latter was in turn the son of Robert I of Dreux, a younger brother of Louis VII "The Young", king of France. Pierre was thus of the Capetian royal house, and a second cousin of Louis VIII "The Lion", king of France[51,67]. |

| DEATH | Pierre died either in May 1250[19], on 22 June 1250[44] or on 6 July 1250[69]; he was 59[44]. |

| HIS NICKNAME | He was also known as Pierre De Braine or Pierre Mauclerc[19,45]. As the second son (cadet) of a noble family, Pierre was expected to prepare for and follow a career in the Church (the oldest son became lord of the manor, the second son went to the Church, the younger sons were to become soldiers & knights). It was during his preparation for this life that he earned the nickname "Mauclerc" or "Malclerc", meaning "Bad Clerk". It is not known if this referred to a bad temperment or incompetence at the clerical duties that were part of the ecclesiastic life; but, given his later actions in life, it was probably the former[51,67]. |

| TITLES |

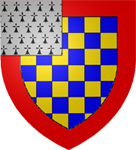

Even if he had not gone into the Church, his cadet status would have meant that he had few prospects in life and

only the few appanages due a minor noble. In his case, he had a few small fiefs scattered around Champagne & the

Île-de-France[67]. When he left the life of the church, he added a remembrance of this lost life

to his coat of arms by adding ermine to a top quarter of his family's coat of arms. Previously, ermine was reserved

for exclusive use of the clergy. (Perhaps inspired by this, in 1312 the arms of the Dukes of Brittany were officially

coded as the only one-word description in heraldry: simply, "ermine".)

However, after the disappearance of Arthur I, Count of Brittany, Philippe (Philip) II "Augustus", king of France, cast about for a ruler strong enough to maintain Brittany for France, but not strong enough to either grasp for more power in his own right or turn to King John of England. Brittany was geographically important to France. It was between the sea lanes between England proper and the Angevin territory of Gascony. In addition, it did so without bordering on either Anjou or Normandy, so it would be difficult to use as a base for an English invasion of France in the wars to reclaim the Angevin lands on the continent. After Arthur's disappearance, Phillipe II worried about the stability of the duchy. Guy de Thouars had been acting as regent for his infant daughter Alix, but was not strong enough to keep the powerful Breton barons in check. To further complicate matters, no-one knew for sure if the beloved Arthur was actually as dead as the rumors said AND his older half-sister Eleanor was in the hands of the English King, John. So, Phillipe tapped his young cousin and arranged a marriage between Pierre and Alix de Thouars. Pierre was in his early twenties and Alix was 3; but this was normal for the purely political nature of these noble marriages. The marriage took place around 23 January 1213 and Pierre did homage to Philippe as his liege lord for the title of Count of Brittany (comte de Bretagne) on 27 January 1213[67]. Thus, Pierre became Count of Brittany Pierre was Count of Brittany in right of his wife from 1213-1221)[19,24,43]. After wife Alix' death, he became regent for his son from 1221-1237; but, in actuality, he ruled Brittany as he had before until his son Jean (John) came of age[67]. Pierre was also made Earl of Richmond (1st and only Earl of the 2nd Creation of the title) in 1219[68], probably as a bribe from King John (see below). The pairing of the two titles was somewhat traditional and lasted through the Breton War of succession until the link was broken during the Wars of the Roses. Pierre held the title of Earl of Richmond until 1235 when, like many nobles of the period, he was forced to choose which country to whom he pledged allegiance: England or France. Ironically, Pierre chose France and thus forfeited his English lands & title[68]. |

| BIOGRAPHY |

Pierre's elevation to count brought out the "mal" part of his nickname and his character. Perhaps because he had grown up as a younger son with no expectation of prospects, tastes of power and lands only increased his appetite for both. As Philippe "Augustus" had hoped, Pierre kept a tighter leash on Brittany than his father-in-law Guy of Thouars. However, he quickly became high-handed and selfish about running the duchy[51]. For instance, he would pull down all the houses in a parish (or group of parishes) in order to use the material to build up the ramparts of one of his castles. Legend has it that he once threatened a priest who refused to bury a usurer crony of his (the Church would not allow burial of a usurer in consecrated ground) that he himself would bury the priest alive with the man's body unless Pierre got what he wanted[51]. Despite his priestly training, he spent most of his adult life fighting with the clergy around him and defending himself from their charges in the ecclesiastical courts in Rome[51]. For the independent & freedom-loving Bretons, he was an unwelcome change from Guy de Thouars. Early in his career as count, he was quite loyal to his kinsmen in the royal family of France. He fought beside Philippe Augustus against the incursions of the English and fought beside Louis VIII "The Lion" in Flanders, Anjou & England[51]. For example, in 1214, Pierre drove off King John from Nantes on the southern edge of Brittany during an English invasion to reclaim Angevin lands. But this brief skirmish showed the first cracks of duplicity and private scheming on the part of Pierre. For while Pierre won the confrontation at Nantes, he did nothing to hinder John's subsequent movement up the Loire valley, nor did he make arrangements for the release of his brother Robert, who had been captured at Nantes. Recent scholars have postulated that an agreement between the two possibly explains John's inexplicable attack on Nantes by the most well-defended approach (thus guaranteeing defeat) and Pierre's subsequent inaction as John took one Breton fortress after another in the Loire. Perhaps it was an agreement that John would leave Brittany alone for now and in return the Bretons would not hinder his movement in other French lands[46,47,48,67]. It was at this time that King John offered Pierre the earldom of Richmond. It was considered a great English honor and had traditionally been paired with the dukedom of Brittany. The wars over Angevin lands in France after the death of John's father, Henry I, and his firm hand over the vast kingdom of England and most of France had broken the tradition of awarding one with the other. But it was well known that Pierre strongly desired to receive the copious English revenues from Richmond[67]. At first, Pierre did not take John up on his offer of Richmond, which would have meant he would have to take John's side in his ongoing problems with the English barons. It could be that Pierre did not think John would last on the throne or perhaps that he still felt that he needed to curry favor with his current liege Prince Louis IX, who was once again fighting an English invasion. However, when John's son Henry III, king of England scored a rare defeat of Louis IX in 1218, Pierre was sent as one of France's negotiators for a peace treaty. He took young Henry up on his father's offer and after the negotiations were concluded, William Marshal (regent for Henry III) officially recognized Pierre as Earl of Richmond. For political reasons, Pierre did not receive the center of the earldom's traditional properties in Yorkshire, but instead received better lands outside Yorkshire which generated the bulk of the earldom's revenues[67]. The visit to England to survey his dukedom of Richmond thoroughly corrupted him. It was at this point that Pierre tightened his grip on Brittany and increased the power of the traditionally weak Breton count. He wished to bring the office's power & authority to the level of Capetian northern dukes (limit castle-building by his barons, claiming right of guardianship of his vassals' minor heirs, etc.) Rather than using patience and political maneuvering, Pierre simply declared the new rules to be in effect immediately and dealt with the predictable wrath of his barons. However, by 1223, the Breton barons had either agreed to the new rules or been dispossessed of their lands[67]. Pierre had less luck bringing the six bishops of Brittany in line with his definition of ducal power. They each held vast lands, including most of Brittany's cities, and had no intention of either allowing Pierre to raise taxes in their areas or to take possession of all the ecclesiastical lands in his duchy. Pierre insisted on imposing his will upon the episcopal lands and was duly excommunicated from 1219-1221 for his pains (a serious punishment for a leader, for it meant that nothing Catholic could go on in his lands; no ringing of the hours to measure time, no baptisms, marriages or last rites. No official church services for all his vassals). Pierre finally capitulated and the ban was lifted, but this was only the beginning of his conflicts with the Catholic church[67]. Nonetheless, Mauclerc answered the call of both Church and Philippe Augustus' son Louis VIII "The Lion", king of France to take part in the Albigensian crusade against the Cathars of southern France[50]. In the early part of this long war, he participated in the 1219 battle of Marmande & siege of Toulouse[69]. He followed Louis back into the Albigensian fray by heeding Louis' call for his vassals to meet at Bourges, France in spring 1226[50]. When Louis VIII "The Lion" died, a rumor made the rounds that Robert I of Dreux had, in fact, been the older son of Louis VI "The Fat" of France and not the younger. According to this gossip, Louis VII "The Young" was vaulted over Robert I for the throne because Robert was "duller" than Louis VII. Were this to be true, Robert I de Dreux should have been king of France. Thus, when Louis VIII died in November 1226, Pierre de Dreux decided it was time for him to press his slim claim for the throne of France based upon this rumor[34]. Queen Dowager Blanche knew that Pierre was no longer an ally when did not attend the coronation of her son Louis IX "The Saint". Pierre was able to persuade two other missing nobles from Louis IX crowning to support him: Theobald IV "Le Troubadour", count of Champagne (later Theobald I, king of Navarre) and Hugo (Hugh) X "Le Brun" de Lusignan. Henri (Henry), count of Bar had been at the crowning, but soon came to his brother-in-law Pierre's cause. The rebels moved their forces against those of the French court[33,34]. Blanche of Castile, Queen Dowager and regent for her eleven-year-old son & king, Louis IX "The Saint", moved quickly. She proved to be the people's queen and by the end of January 1227, her vassals had rallied around the two of them. This first wave of support included Philippe Hurepel (half-brother of Louis VIII) and Robert "Gâteblé" (brother of Pierre). This army moved on Pierre at Thouars, where Pierre had gathered his army[34]. There, the rebels named the honey-tongued Theobald as their chief negotiator, but it was soon apparent that he was infatuated with Queen Blanche and was drawing out the negotiations in order to simply spend time with her. Pierre sent Henri of Bar with Theobald in order to keep the chief negotiator on task; but when Richard of Cornwall tried to ambush them after a round of negotiations, they ran back to Blanche and begged for asylum[35]. Finally, Pierre & Hugo (Hugh) X de Lusignan had no options left but to capitulate to Blanche and sign a treaty on 16 March 1227. The negotiations were concluded with the usual round of betrothals of children of the principals (see below) and this uprising was concluded without shedding a single drop of blood on the battlefield[36]. Pierre seethed about this outcome and planned revenge against both Blanche & Theobald. His new plan was to embarrass Louis IX into cutting the apron strings with Blanche & turning to Pierre & Hugo (Hugh) for influence[36]. Pierre had not reckoned on the pubescent king having enough acumen to barricade himself inside the castle at Montlhéry when warned of Pierre's approach and sending a messenger to summon his mother for help. She had no time to summon her vassals, but appealed to the people of Paris to rescue their king. The sight of this people's army coming to the aid of Louis IX made Pierre's army disperse of their own accord[37]. Blanche & Louis IX then returned to Paris through a gauntlet of cheering people[38]. Despite this second defeat and the clear support of the people for Louis IX, Pierre's faction of barons tried once again to topple the king & his Regent. This time, they turned to slander: a foreigner (Blanche, who was from Castile) was running the country and she was having an open affair with Theobald, count of the Champagne. These were but two of the calumnies that his group spread[39]. This tactic met with some success. Philippe Hurepel (half-brother of Blanche's husband Louis VIII) and Enguerrand III of Coucy (kinsman to the Dreux family) joined the rebel cause. Pierre and his cronies appealed for help to the English king Henry III. Blanche appealed to the common folk and burghers of the French cities[52]. Pierre & his cronies planned to answer their liege's call for a seigneurial host by appearing before Blanche & Louis with two knights each; thus, fulfilling their oath to her, but leaving her with an army of nearly none[53]. The supporting barons waited for Pierre's signal to attack the royal host. This sign was the refusal of Pierre to answer Louis' summons to Christmas court on 31 December 1227. But before the rebels could act, Blanche marched her own army into Pierre's lands. To the surprise of the rebel cabal, Blanche's army was huge and smack in the middle of it was fellow conspirator Theobald of Champagne; not with the promised two knights, but with 800[53]. Louis IX himself executed the bold plan of marching straight for Pierre's strongest fortress of Bellême while the latter was busy harrying royal lands (Pierre had not expected a countermove until spring 1228). He and Blanche were able to get the garrison to surrender peacefully in January 1228 after a mere two days of siege and this proved to be the key. Castle after castle in Mauclerc's lands surrendered to Blanche with virtually no bloodshed[54]. Pierre's ambitions were thwarted again. Mauclerc immediately turned his wrath against Theobald of Champagne, who Pierre considered a traitor to his cause. Theobald was an easy mark at this time. Since the unexpected death of Louis VIII, rumors swirled around the French court that Theobald had poisoned the king. Rumors still abounded from Pierre's previous slander campaign that Theobald was sleeping with Queen Blanche (almost assuredly false tales, but they have stuck until today). In addition, Theobald was no politician. He had managed to anger the powerful Hugo (Hugh) IV, duke de Bourgogne (of Burgundy), the archbishop of Lyons (who Theobald kidnapped) and Henry, count of Bar (who rescued the archbishop). Although not yet 30, his corpulence was the subject of court jesters & poets[55]. The count of Nevers and Henry IV, duke de Bourgogne (of Burgundy) were the first to invade Champagne. Blanche rode at the head of an army which rode to Theobald's aid. Philippe Hurepel & Hugo (Hugh) IV de Bourgogne (of Burgundy) quickly ceded to Blanche and the open rebellion was over. Instead, each baron took their individual grievances to the royal court and each asked for the right to settle their quarrels with the count of Champagne with judicial combat. So many, in fact, that Louis IX declared the practice illegal and obsolete[56]. Yet, Pierre would still not give up his slim claim to the throne of France. In October 1229, he resorted to outright treason and sailed for England. There, he convinced Henry III, king of England that the time was right to invade France and recover the Angevin lands lost by Henry's father, King John. Henry III & Pierre planned an invasion for Easter 1230[57]. Unbeknownst to Pierre, Blanche & Louis IX were already making preparations for the defense of France. One by one, Blanche used diplomacy to convince Pierre's allies to side with Louis (even his in-laws, Gui (Guy) and Raimond (Raymond) de Thouars). So, when Henry invaded France, the invasion quickly fizzled out and Henry returned to England[58] and Pierre was forced to sign a 1231 treaty with Louis IX. Amazingly, Pierre still did not give up his claim. Now he was the subject of unflattering jests, poems and ballades[59]. Pierre's reputation was soon undermined in the important courts of France. Blanche now went on the diplomatic offensive and worked tirelessly to keep Mauclerc isolated and thus defuse the most serious threats to Louis IX. She obtained fealty for her son from all the castellans ruling castles that bordered Brittany. She obtained Amaury de Montfort's complete support by making him Constable of France and getting him to agree to be rid of conflict of interest by ceding his lands and title in Leicester, England to his younger brother, Simon[60]. Blanche's efforts seemed secure until the ever-inept Theobald of Champagne announced his betrothal to Pierre's daugter, Yolande. She was Pierre's favorite commodity and bargaining chip. In 1227, Pierre had betrothed Yolande to Louis IX's younger brother Jean (John) in the usual round of betrothals used to seal a treaty. This not only bound by marriage two previously warring families; but, in this case, Jean was to receive Anjou & Maine and Pierre coveted control over those properties. But Pierre then broke the treaty with another attempt at the throne and the betrothal was null and void[61]. (The young prince Jean died in 1232 at age 12, anyway.) Now, he had betrothed his daughter to Theobald in an attempt to build a new coalition and stashed the girl away at the nunnery of Prémontré en Valsecret ("in the secret valley") until the marriage could take place. Blanche's plans for isolating Pierre would be dashed by this marriage and she pulled out the big hammer to use on Theobald. On his way to visit Yolande at Valsecret, he was stopped by a messenger of Louis IX who delivered a crystal clear message: if Theobald married Yolande, the king would dispossess him of all he owned in France[62]. Theobald was stunned, but prudently withdrew from the betrothal and married Marguerite (Margaret) de Bourbon instead. He later discovered that Pierre had offered Yolande to Henry III of England at the same time he had been betrothed to the girl[62]. That marriage did not take place because the papal dispensation needed in order that the two might marry never arrived. The betrothed were within the prohibited number of degrees of consanguinity[51]. Four years later, Theobald - now King of Navarre by virtue of succeeding his uncle Sancho VII - sought to wed his daughter Princess Blanche chose a groom who, on paper, was perfect: Jean (John) I "Le Roux", duke of Brittany. In reality, this proved to be yet another poor choice by Theobald. Louis IX and his brothers Robert I, count of Artois & Alphonse showed up on Theobald's doorstep with an army to force a break with the family of Mauclerc. Theobald instead appealed to the Pope and, with the Pope's backing, headed to Louix IX's court to make peace with the king. Just as he was about to enter Louis' audience chamber in all his finery, Theobald was doused with sour milk in a bit of revenge orchestrated by the 15-year-old Robert I of Artois to pay him back for all the insults his mother had suffered over the years because of Theobald's unwanted attentions and political mis-steps[63]. After this, Theobald left France for good, but his reputation found redemption in the Holy Land[64]. In his later years, Pierre's motivations changed. His wife Alix' death in 1221 meant that his son Jean (John) I was now officially duke of Brittany even through Pierre ruled as regent for 16 more years until Jean reached his majority in 1237[67,69,73]. This meant that Pierre had to acquire lands for himself outside the duchy so he would have somewhere to retire when his son came of age. He also needed to be sure that his actions would not result in the loss of lands, title or prospects for his son. So he mended fences and took up the cross again in 1240 and, when he returned to France, won significant maritime victories against the English in 1242 & 1243[69]. Finally, from 1247-1249, Pierre joined Louis IX for the ill-fated Seventh Crusade against Egypt[65,69]. Pierre died while returning from this last crusade[69]. |

| MARRIAGE #1 |

Before 23 January 1213 when Pierre (Peter) I was 22, he first married Alix (Alice), Duchess

DE THOUARS[70,71], daughter of Gui (Guy), Count DE THOUARS (see de Thouars) &

Constance, Countess OF BRITTANY & RICHMOND[43,67,72]. We know it was just before this date,

because that is when Pierre did homage to Philippe Augustus, King of France for Brittany. Alix was born in 1201[73] and

died in childbirth on 21 October 1221; she was 20[44,67,73].

Alix was Duchess of Brittany from 1206 to 1221[19,43,44]. She became Duchess of Brittany by virtue of being half-sister to Arthur & Eleanor of Brittany. King John of England had hoped to gain control of Brittany by "disappearing" Arthur and imprisoning his full-sister Eleanor. Instead, he lost the duchy to Alix de Thouars and her marriage to Pierre de Dreux started a new Breton dynasty which lasted until the end of the 1400s[74]. In 1206, Philippe Augustus, King of France, installed her as duchess of Brittany with himself as regent. Thus, it was Philippe who arranged her marriage to Pierre de Dreux in 1213[73]. |

| CHILDREN | 31. | i. | Yolande DE DREUX |

Yolande was born in 1218 and died in 1272; she was 54[43]. Yolande was Countess of Penthiévre[43].

In 1235 when Yolande was 17, she married Hugo (Hugh) XI DE LUSIGNAN[82,83,84], son of Count Hugo (Hughes or Hugh) X "LE BRUN" DE LUSIGNAN, count of La Marche & Angoulême & Isabella OF ANGOULÊME, countess of Angoulême & queen of England[43]. Hugo (Hugh) was born in 1221 and died in Egypt (probably at the Battle of Mansurah) in 1250; he was 29[81]. Hugh was Count of Ponthieu, La Marche (1249-1260) and Angoulême (1249-1260)[81,29]. They had the following children (surnamed Lusignan): i. Alix (Alice) ii. Marie (Mary) iii. Hugo (Hugh) XII |

|

|

32. | ii. | Jean (John) I DE DREUX | Please see his own page. |

|

|

33. | iii. | Arthur II DE DREUX | Arthur was born in 1220 and died in 1223 or 1224; he was 3[43]. |

| MARRIAGE #2 | In 1235 when Pierre was 44, he second married Marguerite (Margaret) DE MONTAGU[72]. |

| CHILD | 31. | i. | Oliver DE DREUX | Oliver was born in 1221 and died in 1279; he was 58[43]. He was also known as Olivier I de Braine as was seigneur de Machecoul[69]. |

| GENERATION | TBD |

| FAMILY NUMBER | TBD |

| SOURCES |

1. Edward Carroll Death Record,

19 October 1899, Lynn, Essex co., MA,

1866, 192, p. 186, #337.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Return to the de Dreux Index page. |

|

| Return to the Family Index page. |

|

Return to the Surname Index page. |

|

|

Return to the Maddison Side Tree page. |

|

all the content on this page is copyrighted ©1992-2007 by Kristin C. Hall.

many thanks!

SPECIAL THANKS TO

please drop me a line, if you wish to use it or link to it. kattyb.com for the nifty background! Check our her sites, they are terrific!

kattyb.com for the nifty background! Check our her sites, they are terrific!